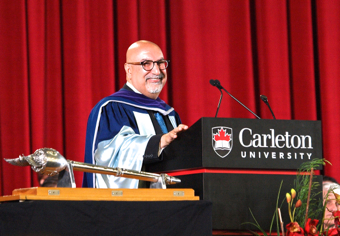

CARLETON UNIVERSITY CONVOCATION SPEECH

The following is the video and text of the convocation speech delivered by Firdaus Kharas after receiving an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Carleton University on June 11, 2015.

Ottawa, Ontario

June 11, 2015

By Firdaus Kharas, BA, MA, LLD, DHum

Mr. Chancellor, Mr. Chair of the Board, Madam President, Honored Guests, and the most important people here today, Graduands:

I am deeply touched and humbled by this very high honor. I would like to thank the Senate of Carleton and Dr. Runte very much for this honorary degree, which I shall cherish for the rest of my life. This recognition is not just for me but is shared by many people, including a thousand volunteers, who have joined with me in a quest to better the human condition using mass communications.

This is a celebration not of which jobs I’ve had but of who I am. Who I am is who you can be. Let me explain.

Today is a major milestone in my journey, a journey marked with successes and failures, a journey that has taken me from India to the United States to Canada. It is not a path that has always been clear to outsiders but has always been clear to me.

For better or for worse, it is a life filled with trying to prove what others say can’t be done, can be done; to being out in front as a disrupter; to continually reaching beyond my grasp; to fulfilling my dreams.

When I told people 20 years ago I was going to start what I called a “hybrid company” using proceeds from for-profit media projects to fund non-profit media for social change across many cultures and that I would give away my work for free, more than one accountant and international affairs expert gave me a highly quizzical look! Today there are hundreds of thousands of companies combining profit with doing good and you studied them as ‘social enterprises’.

So today if you’re feeling a little left out or you’re a bit of a maverick or you’re passionate about something that isn’t readily understood or embraced by those around you, don’t worry – your originality and tenacity might be enough to get you back here in 35 years to receive an honorary doctorate!

When I was quite small, perhaps eight, I was taken to meet Mother Teresa, who was then unknown outside of my birthplace, Calcutta. The image of Mother Teresa working in a huge room with the poorest of the poor dying on cots is still etched in my mind as if it were just yesterday. Looking back, I know I grasped then the importance of living and working outside of one’s comfort zone for the benefit of others.

It manifested itself later in Bombay when my best friend and I taught in a slum every Saturday to whomever attended. We taught whatever we were learning at the time in our very elite high school. Our school was not very far physically from the slum but was light-years away in every other aspect.

From India I went to study in Pennsylvania, from where I first visited Carleton in 1977 while still an under-graduate student. At that time the Director of the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs was Dr. John Sigler. During the course of a fairly brief conversation, he persuaded me to apply to Carleton, offering a full scholarship. That conversation with John Sigler changed my life and I am forever deeply grateful to him. I want to mark today with deep respect and tribute for him.

It turned out to be not just a matter of spending a couple of years in Ottawa getting a degree: I subsequently settled down here and had a family. Yesterday my son received his second degree from Carleton and tomorrow my daughter will graduate from the University of Ottawa.

I lived in Glengarry House here on campus for a year. I don’t recall stepping out of the tunnels too often for an entire winter. Except once, when I walked on the canal… and put one foot through it. Hey, I was then a foreign student from India with not a lot of experience walking on ice!

Overall, I had a great time at Carleton but I had to confront some skepticism. I wrote my Master’s research essay on a draft international convention against the use of torture. To be honest, it was not very well received. The examining board couldn’t understand the nexus between what I was studying — Conflict Analysis — and human rights. You see, the concept of human security was not yet born and a link between the widespread abuse of human rights and political instability was a novel idea back then.

Nine years later the United Nations Convention Against Torture came into effect. Today, there is a standard to which governments can be held and that courts can uphold. People now know they have a right not to be tortured. There are many less people being tortured today than there were in 1979.

My research at Carleton wasn’t just about drafting a legal document. It was much broader, on the reasons to have a convention: to further the notions that people everywhere mattered, that they have fundamental rights as human beings, and that they can expect assistance when they are abused, no matter where they are located.

I have always believed that our shared commonalities as human beings affirm that we will not tolerate mistreatment or injustice; that if we can save a child’s life, we should; that if we have an ability to lift a person out of the crushing burden of scarcity and poverty, that is our duty; and that if we have the talent to affect change for the better, we must use it.

I’m having a lot of fun! I do what I do because I live with a great sense of hope and I have boundless optimism.

If you look just at the daily headlines about what is happening on our planet and aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand the data. However, if you meet the many people who are working to keep this earth beautiful and are endeavoring to enrich the lives of all of us, and aren’t optimistic, you haven’t got a pulse.

Having traveled to over 130 countries, what I see everywhere are ordinary people willing to confront difficulties and incalculable odds in order to bring about justice, progress and joy.

So many have inspired me and aided me over the years. There are many in this room and I thank them profusely; others are far away.

I think of the old bearded man in India who came every week to our school in the slum to learn in a classroom for the first time.

I think of the Roman Catholic priest who defied his Pope by giving voice to our HIV/AIDS campaign promoting the use of condoms because he thought it was the right thing to do to save lives in Africa.

I think of Archbishop Desmond Tutu who supported my work. I wrote to him worried that I had caused him embarrassment because he was dragged into an attack on a very well known right-wing American radio show. He responded with his usual grace and humor by telling me to “put on my tin hat and get back in the trenches”.

I think of the young boy I interviewed in Bangladesh for a documentary who was trafficked at age three to the Middle East as a child camel jockey. When he finally returned to his home country, he couldn’t find his family because he didn’t know who they were, but he continued to search, village by village — with hope.

I think of the Maasai women in Kenya who took me on a bright sunny day into their hut, which was totally without light inside. I used my flash to take a photograph of the ceiling, which when I saw in my hotel room, almost defied belief: it was pitch black, literally dripping with soot from burning fires and kerosene lamps. A $10 solar light would transform their lives, increasing their wealth and solving their many health problems.

I think of the 12-year old child who awakened in 5am darkness in rural Sierra Leone during the height of the Ebola crisis last year to give voice to our animated video on prevention. He was determined to warn others in his community of the dangers of the deadly virus ravaging his country.

They are the determined, they are the right, they are the meaningful. They are our examples. None of these people live in despondency. They all have embraced their difficulties, risen from their set-backs and now make a difference.

No matter where we are, we can motivate and help each other. Innovation and technology are changing our way of thinking and of doing. Twenty years ago when I started my work in using mass communications to better the human condition, the world was only able to receive information passively through TV and radio. We are now at a new point of human history, which has opened up endless opportunities to use information for development: an age of global, instant, widespread, personal, two-way communications. The world has therefore become a much smaller place.

My work rests on a deeply-held belief that we can meaningfully communicate with each other despite the many barriers that separate us: languages and cultures, tribes and ethnicities, geographies and borders. We have forgotten the commonalities that we have as a species and have instead accentuated the differences like culture and religion. I am convinced that modern communications can greatly assist us to bridge our differences, creating knowledge and understanding of each other to return us to the concept of one human family.

At a press conference at the United Nations I gave to launch the Buzz and Bite malaria prevention campaign I was asked by a journalist if there is any issue that could not be made better through mass communications. I thought for a while and said no, I could not think of any such issue. Some will take shorter and some will take longer but all can be positively impacted. I am confident, for example, that with mass awareness of prevention methods, the greatest killer on our planet, the mosquito, will be defeated and malaria will be wiped out in our lifetimes.

Graduands, it’s an exciting time to be alive, even more so when you have more tomorrows than yesterdays. For those of you ending your studies today, now, at last, you can begin.

You are armed with a very good higher education. It doesn’t matter what you studied, you have the power to affect change, the power to create happiness. This is your time.

If you stay focused on your goals, you will succeed. All it will take is a deep passion for what you want to achieve and a profound belief in yourself. Above all else, don’t listen to anyone who says it can’t or shouldn’t be done.

My generation now turns to you. As you go forth into your careers, my plea to you is to keep our collective hope alive.

Let me propel you forward by telling you what I have discovered: the great truth of the human experience is that being selfless, kind, caring and generous are the best things you can do for yourself. So I’m asking you not just for the others that you will help, but also for your own wellbeing.

Congratulations, graduates. Go out there and have a truly wonderful life!

Thank you so much for allowing me to be a part of your very special day.